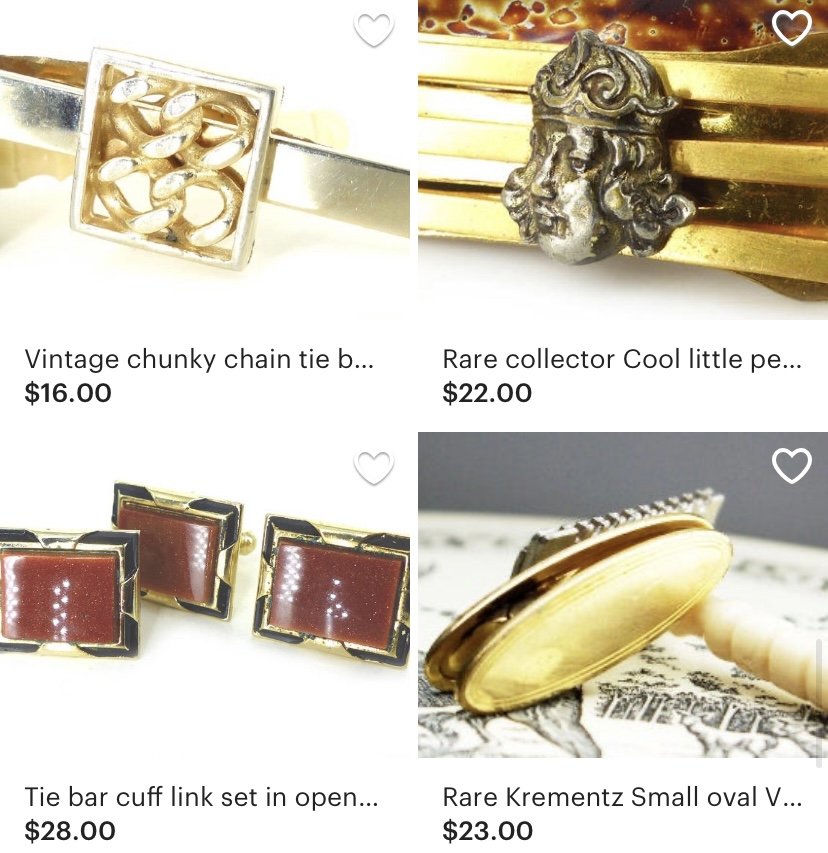

May 1851. London was abuzz with excitement at the opening of a new international exhibition of trade and commerce in Hyde Park. Travellers crammed onto the many horse-drawn buses that served as the city’s public transport system, and craned their necks as they swept along Knightsbridge, anxious to catch a glimpse of the Crystal Palace that had sprung up in one of London’s largest public spaces.

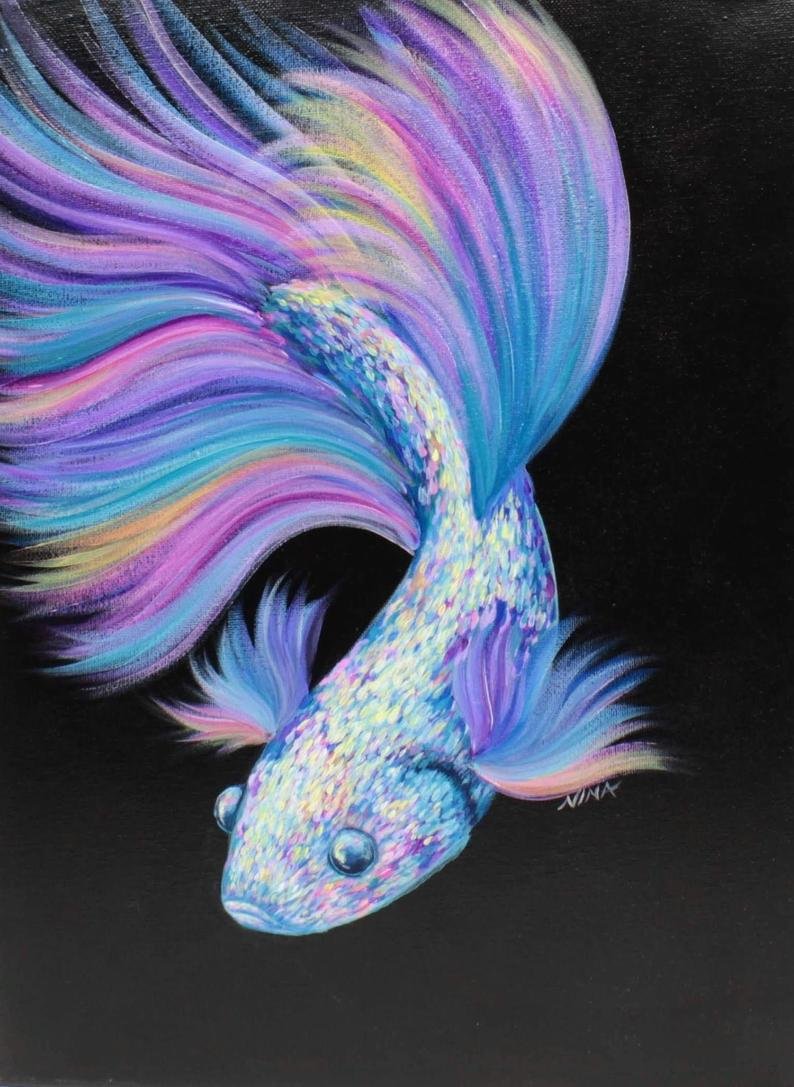

Glittering in the sunlight, it was truly a sight to behold. The first prefabricated building of its kind, the enormous glasshouse incorporated 300,000 sheets of glass in the largest size then ever made, held in position with some 24 miles of patent guttering. In just nine months, this magnificent building had become a shining landmark on the capital’s skyline.

The Exhibition was the brainchild of Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, and Henry Cole, an English civil servant, inventor and member of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (now known as The Royal Society of Arts). Prince Albert, himself an enthusiastic promoter of British manufacturing and industry, as well as a determined moderniser, became patron of the society from the 1840s, and the pair developed an idea for a great international show: “for the purpose of exhibition, and of competition and encouragement”.

Exhibitions of this kind were not unusual during the 19th century. Cole himself had visited the French Industrial Exposition of 1844, in Paris, and had returned full of ideas for a British show – one that promoted British superiority and its position as a world leader in industry, but that also encouraged other nations to display their own achievements.

The Great Exhibition was a defining episode in Albert’s life and the setting for the season 3 finale of ITV’s Victoria. (Image by ITV/Shutterstock)

How was the Great Exhibition planned?

An exhibition of the magnitude and scale that Albert and Cole were planning needed an equally impressive venue, and a design competition was launched for a building to house the Great Exhibition. Some 248 plans were submitted, some- by French architects, but ultimately the exhibition’s Building Committee – among them renowned engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel – decided that they could design something better. Despite the unethical nature of the decision, in May 1850, the committee produced its plan. It did not receive a positive reaction. The proposed redbrick building would have taken 15 months to build and required some 15 million bricks – with the opening day of the Exhibition scheduled for 1 May 1851, it was hardly a viable option.

While debates were raging as to where the Exhibition could be housed, one man had taken matters into his own hands. Joseph Paxton – a gardener, but also something of an architect and designer who had built greenhouses for the Duke of Devonshire’s home of Chatsworth, Derbyshire – had devised his own palatial idea for the Exhibition. What’s more, rather than leave things to chance, he had already shared his plans with the London Illustrated News, which had declared its own support for the design and shared the plans with the British public. By the time the idea had been brought before Henry Cole and the committee, let alone Prince Albert, Paxton’s design had already garnered widespread support. Added to the fact that the proposed building would take no more than ten months to erect, could be fabricated off-site and dismantled after the event, it’s small wonder that Paxton walked away with the commission. The London Illustrated News, too, did rather well out of championing Paxton’s design, selling 100,000 copies in the week the Exhibition opened, and printing a number of special supplements, with fold-out engravings of the building and its contents in the run-up to the big event.

Glittering in the sunlight, it was truly a sight to behold. The first prefabricated building of its kind, the enormous glasshouse incorporated 300,000 sheets of glass

In August 1850, work began on Paxton’s magnificent Crystal Palace – a named coined by playwright Douglas Jerrold. By December that year, some 2,000 men were working on site, piecing together 8,000 panes of glass every week and erecting the 1,000 cast-iron columns needed to support the structure. One can only imagine the fascination felt by Londoners as they watched huge steam engines transport exotic exhibits onto the site, and witnessed the building rise before their eyes.

The Great Exhibition opens

The completed building was a sight to behold: 562 metres long, 124 metres wide and towering 30 metres high over Hyde Park – that’s about ten storeys high. Most importantly, this colossal feat of engineering was finished on time. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given her husband’s level of involvement with the project, the Great Exhibition was opened on 1 May 1851 by Queen Victoria, who waxed lyrical about the event in her journal: “This day is one of the greatest and most glorious of our lives”, she wrote. “The Sun shone and gleamed upon the gigantic edifice, upon which the flags of every nation were flying… The tremendous cheering, the joy expressed in every face, the vastness of the building, with all its decoration and exhibits, the sound of the organ... all this was indeed moving.”

The opening ceremony was attended by all manner of dignitaries – from the Archbishop of Canterbury to foreign ambassadors and other officers of state. Some 20,000 season tickets (at a cost of £3 3s for men and £2 2s for ladies) had already been sold in advance, and visitors had been carefully placed around the building, so as to avoid a crush when Her Majesty finally arrived, accompanied by Prince Albert and their two eldest children, conveyed in nine carriages.

More like this

Trumpet fanfares and cannons announced the royal party’s arrival, upon which a choir of 1,000 sang the National Anthem. The Archbishop of Canterbury led prayers, followed by a rousing rendition of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus. As Victoria walked sedately around the Exhibition, great cheers accompanied her progress. Finally, the Queen returned to her specially-constructed dais and declared the Exhibition open. Now, her patient subjects were free to satisfy their curiosity and explore the huge wealth of exhibits.

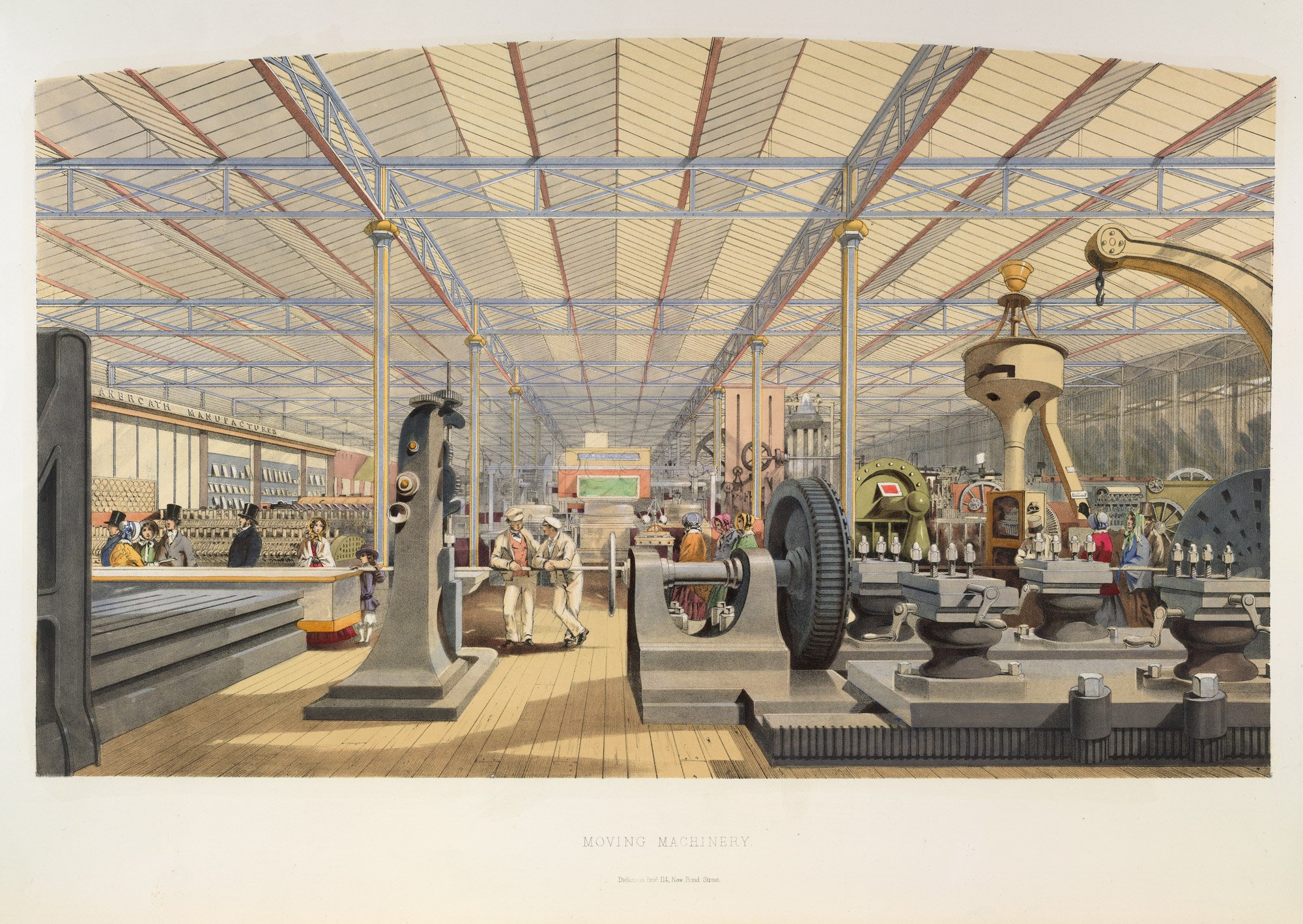

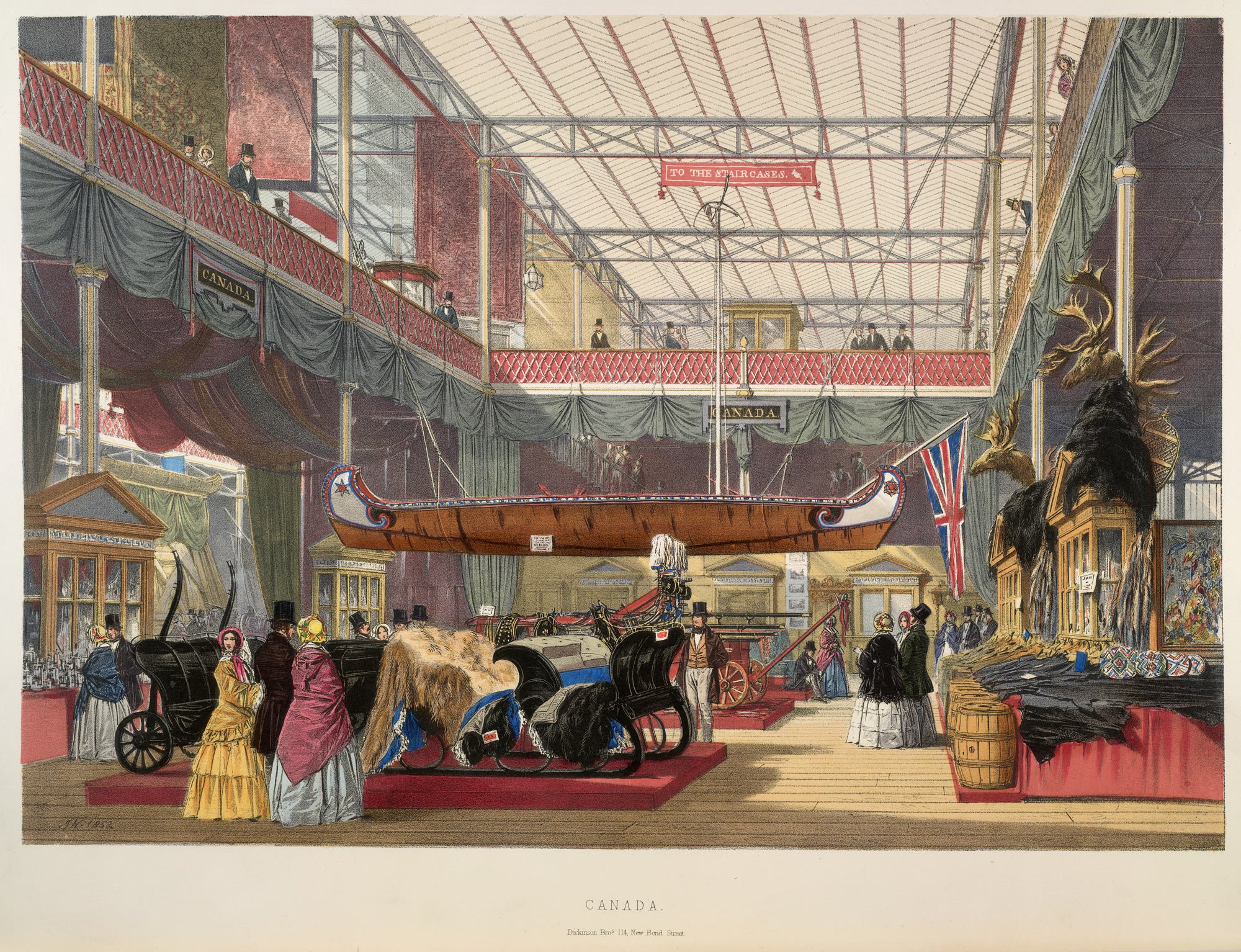

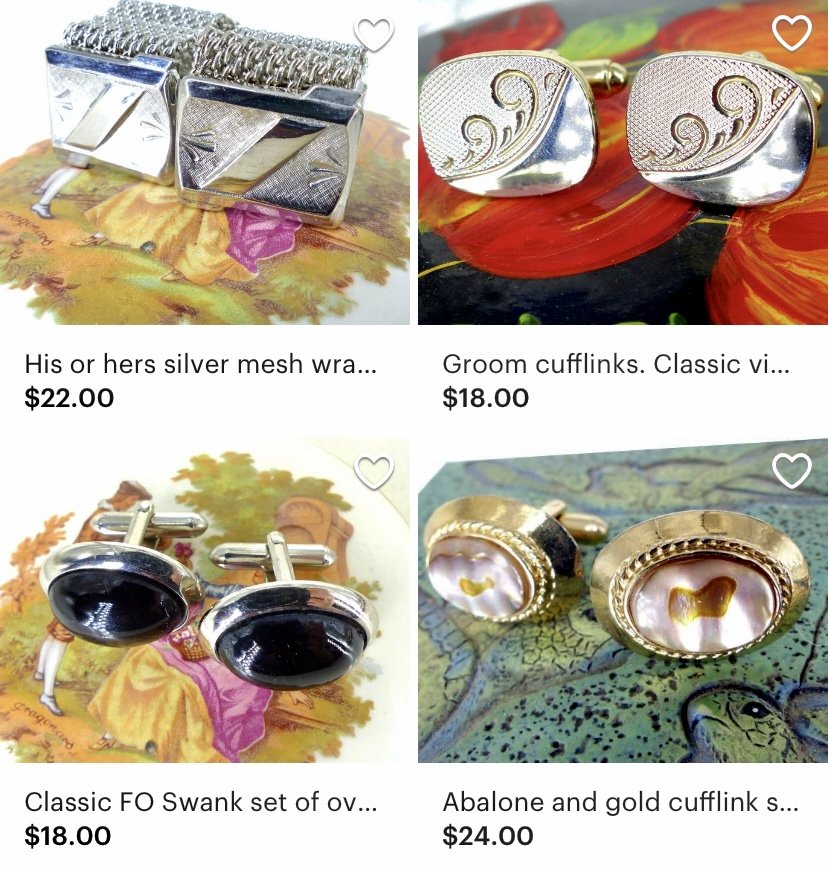

What was on show at the 1851 Great Exhibition?

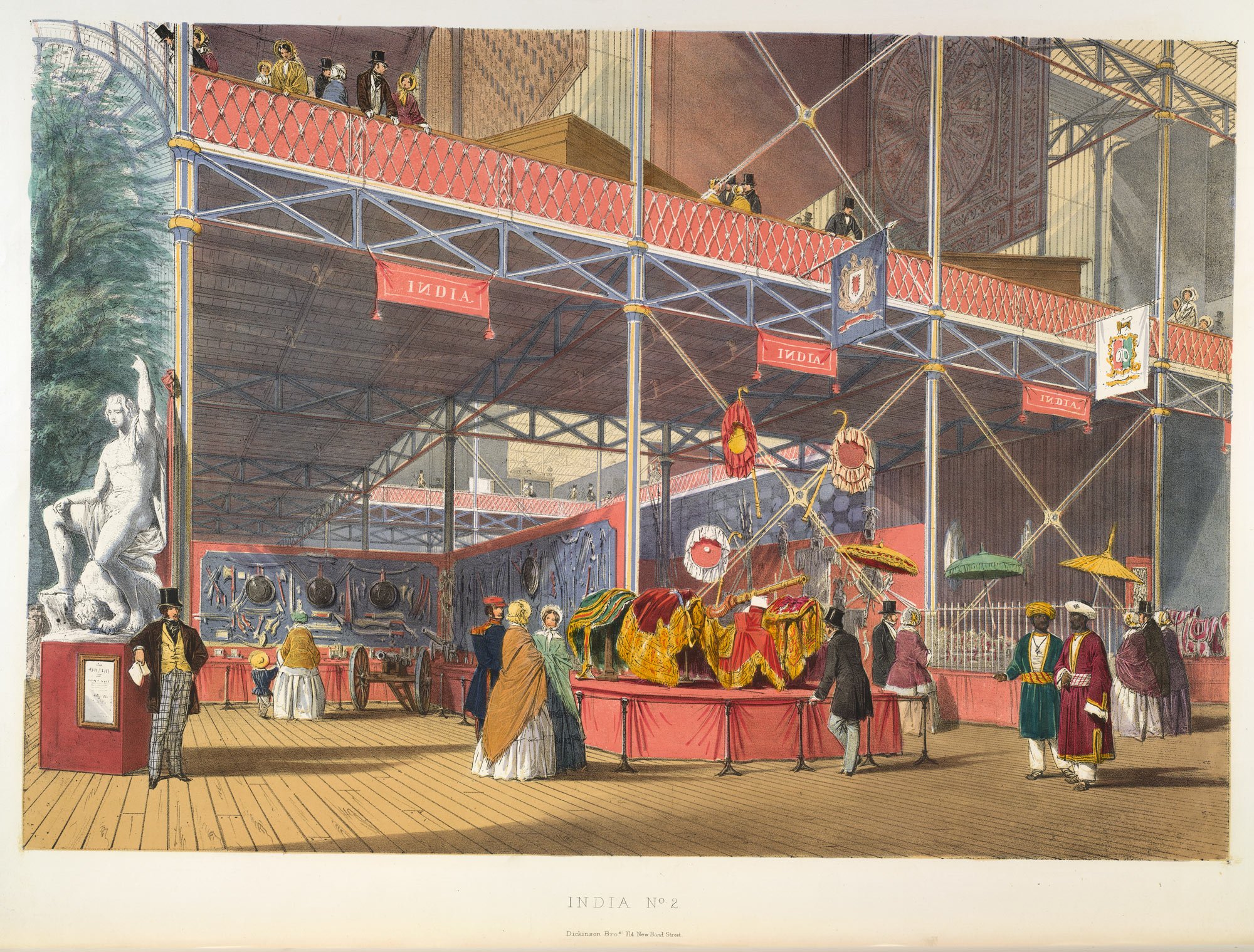

More than 100,000 objects were displayed within the Crystal Palace. As the host country, Britain occupied half of the exhibition space showcasing exhibits from across the Empire. The rest of the building featured objects from some 48 countries – from Russia to Chile. France was the largest foreign exhibitor, flaunting its position as Britain’s main rival in the textiles market with silks from Lyon, sumptuous tapestries, as well as cutting-edge machinery that had been used to produce such treasures. The Russian exhibits, which arrived late as ice in the Baltic delayed their journey, included huge, 3.5-metre-high vases made from malachite, furs and Cossack armour.

Gold watches were displayed in the Swiss space, while Chile sent a 50kg lump of gold. From Denmark, came a single-cast iron frame for a piano, the first made in Europe, while the US sent a giant statue of an eagle holding a Stars and Stripes flag draped around it, along with the recently-invented Bell telegraph.

Arguably the brightest attraction came from India, then under British rule. The Koh-i-Noor diamond – at the time the world’s largest such gem – was displayed in a large cage, lit up on special occasions. The 186-carat stone was of inestimable value but, despite its fame and size, many visitors were disappointed that it failed to sparkle. Nevertheless, the mere presence of the diamond, which had travelled by sea from Bombay (Mumbai), safely ensconced in a small iron safe, attracted much attention. The Koh-i-Noor is at present decidedly the lion of the Exhibition”, reported The Times. “A mysterious interest appears to be attached to it, and now that so many precautions have been resorted to, and so much difficulty attends its inspection, the crowd is enormously enhanced, and the policemen at either end of the covered entrance have much trouble in restraining the struggling and impatient multitude.”

The Koh-i-Noor usually resides in the Tower of London – but ownership is fiercely contested. This image shows a replica, displayed in Bangalore in 2002. (STR/AFP/Getty Images)

Exhibits ranged from the enormous (a full-scale locomotive and a stuffed elephant complete with magnificent, richly-decorated howdah (a seat for two people, covered with a canopy) strapped to it – to the simple.

Condensed milk was one of the exhibits on the British side, a tribute to the modernity and ingenuity of British inventors: city folk no longer had to worry about the freshness of their milk and the length of time it took to reach them. It could now be kept for months.

At the building’s centre stood an 8-metre fountain made of pink glass – an ideal meeting point and a novel way of cooling the air in the glasshouse. For the price of a penny, visitors could pay a visit to the Monkey Closets – the first public toilets, designed by sanitary engineer George Jennings. The lure of a private cubicle and a toilet that flushed, together with the towel, comb and shoe shine included in the price, proved irresistible and 827,280 people visited them in total.

Refreshments provided by Messrs Schweppes could be bought at various locations, although no alcohol was sold. A variety of performances could also be enjoyed during a visit, including cat shows and a circus. There was even a fountain in the Austrian court, flowing with eau de cologne for visitors to sample.

What was the reaction?

The Exhibition was a phenomenal success, despite the reservations of some critics who feared the event would attract radical liberals from overseas. But one of the best aspects of the Exhibition was that it was open to all classes. Entrance fees varied according to the day of visit so, for those on lower incomes, Monday to Thursday was the time to attend, as tickets were just 1s. Thousands took advantage. The price also fluctuated as the Exhibition progressed. By day four, the cost of a day ticket had dropped from £1, to 5s, although it rose again several days later.

For many it would have been their first trip to London, perhaps even their first trip from home and, for them, the Exhibition must have been simply overwhelming. Schoolchildren, factory workers, countrymen and women, dressed in their best smocks, all gazed in awe at what must have appeared an alien world. And they, too, would have caused a stir among the Exhibition’s wealthier visitors, 28,046 many of whom would never have encountered such simple, rural folk. One old lady even walked to London from Penzance, although most took advantage of the rail network. Over the five months that the Exhibition ran for, more than 6 million people visited, each contributing to a final profit of £186,000, which was used to create the South Kensington museums.